Governments, businesses, and nonprofits are increasingly recognizing the importance of diverse perspectives when tackling major social, economic, and environmental issues. But what happens when diversity leads to disagreement?

Specifically: what happens when members of a diverse team, all working toward the same goal, have drastically different ideas about what’s fundamentally right and wrong? About what’s fundamentally important?

This is one of many ethical dilemmas that can arise in Evaluation practice.

A question for evaluators

Dr. Betty Onyura decided to tackle this and other questions in new research that has just been published in the Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation. A researcher at the University of Toronto’s Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, and a past CES-ON Board of Directors member, Dr. Onyura noticed that often, programs designed to solve a specific problem can come up short, or even end up creating new problems of their own.

In trying to get at the root of why well-meaning and well-managed programs can still go awry, Onyura took an evaluation mindset. She found that the teams responsible for designing and delivering programs can have fundamentally different and even contradictory ideas about what’s important in a program, and what the “right” and “wrong” methods look like. Also, when people have different ideas about right and wrong, how can we actually define when something is ethical or unethical? How do we decide what is important or not, or what is of value?

Onyura comes from an interesting perspective to her research. All of her research questions come from her own evaluation work and things that she has wrestled with in her practice.

Building an Evaluation framework

The question of ethics in evaluation has come up before, but usually from the angle of the evaluators’ ideas of ethics – not the program participants’. In fact, Onyura noticed that only a quarter of existing ethics research in evaluation considers the ethical concerns of program participants. Yet the participants are key stakeholders!

This raised other questions for Onyura: What happens when some stakeholder groups are consulted more than others? How does systemic inclusion or exclusion of certain stakeholders affect ideas of what is and isn’t ethical? Furthermore, she saw that many ethical issues aren’t caught by the current framework or guidelines. Those guidelines are not sufficient or rigorous enough!

Clearly, a new framework was needed as an analytical tool to evaluate complex moral situations.

It was time to evaluate evaluation (that pun doesn’t get used often enough!), and through a meta-analysis, Dr. Onyura developed an evidence-based framework for identifying, understanding, and managing ethics.

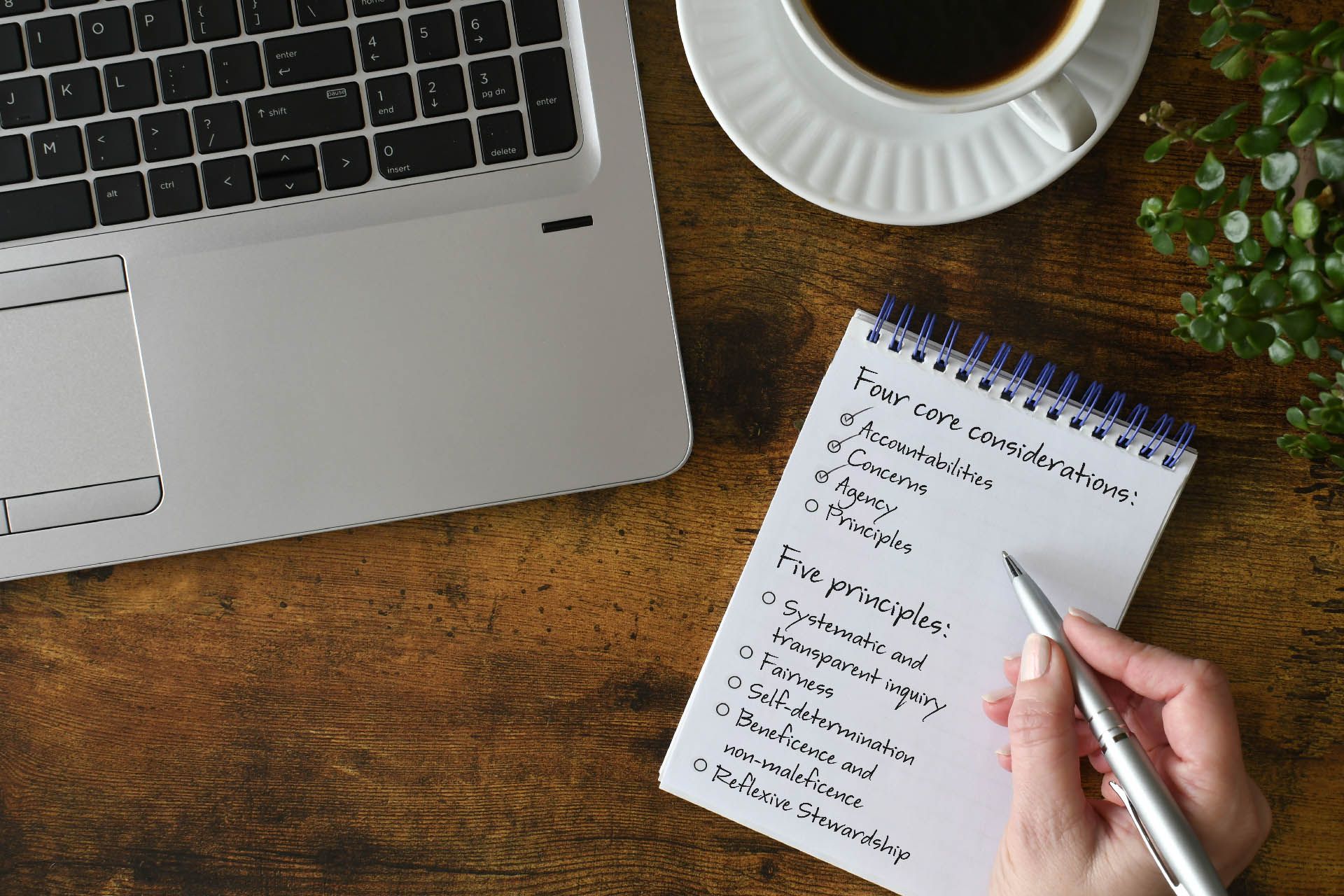

Her framework is built on four core considerations or questions:

1. Accountabilities – To whom or for what do you owe ethical consideration when commissioning an evaluation?

Evaluators can have ethical obligations in multiple directions, including

- Safeguarding both the users and providers of a program

- Servicing client institutions

- Maintaining community and environmental wellbeing

2. Concerns – What issues or behaviours might trigger concerns that ethical considerations are called for?

Onyura found many examples of ethical triggers in her research, including

- Restricting the scope of inquiry into problem areas

- Coercing participation in the evaluation

- Excluding stakeholder groups from participation

3. Agency – Which stakeholder groups have influence in either causing or mitigating those ethical concerns?

Onyura found that evaluators may not always have full control over the evaluation process, and the power dynamics between evaluators, clients, and service providers can play a large role in both causing and mitigating ethical issues.

4. Principles – What ethical principles should be followed?

As a way of responding to the questions above, and based on her research, Onyura sets out five overarching principles that evaluators should follow.

Five principles for ethical Evaluation

Onyura puts forward five principles for any assessment of evaluation ethics:

1. Systematic and transparent inquiry

“Systematic” in that evaluators should be following methods that are technically sound and contextually appropriate; “transparent” in that evaluators must communicate clearly and honestly with stakeholders about the evaluation methods and findings.

2. Fairness

Stakeholder groups must be treated fairly, given equal consideration and opportunity to participate, and the data collected should fully and accurately represent the communities being served by the program under evaluation.

3. Self-determination

Onyura stresses that evaluation participants are not simply test subjects or data points – they’re active partners in the evaluation process and must have agency and self-determination within that process.

Just as a patient seeking a doctor’s professional advice is both a subject of medical evaluation and a key participant, so too are any program’s evaluation participants independent agents with their own priorities and concerns.

4. Beneficence and non-maleficence

Evaluators have an ethical obligation to see that the purpose and outcomes of an evaluation are positive and beneficial for program participants and stakeholders.

Moreover, evaluators must also ensure that any harms inflicted as a result of either the program itself or its evaluation are identified to be avoided or mitigated.

5. Reflexive Stewardship

The results of evaluation on any program can impact local, public, and natural resources. Evaluators therefore have a stewardship obligation, one that requires considering the evaluation’s downstream impacts.

The evaluator must also be “reflexive,” or continuously examining and re-examining how their role, status, authority, and individual biases can shape their idea of what responsible resource management and stewardship looks like.

Conclusion

Onyura’s proposed framework seeks to offer several benefits to evaluators: a tool to cultivate ethical awareness; a system to identify underlying or competing values or issues; a means supporting continued education for Evaluation professionals; and a way to inform consensus-building efforts about ethical principles.

But a framework can only do so much. Onyura’s proposal isn’t a substitute for the need for formal mechanisms and mandates to govern ethical conduct and to incorporate ethics into professional education.

Intentional and coordinated efforts will continue to be required to manage the complexity and competing ethical principles in evaluation. Onyura notes that professional evaluation associations play a key role in ethical practice.

For instance, association members show a greater likelihood of prioritizing ethical standards in the work they perform compared to evaluators who are not a part of an evaluation association. Onyura argues that there’s a clear opportunity for such associations to bring streamlined practices for ethics to the field. (Noted!)

With all of this in mind, what can we, as evaluators, do now? Here are some questions to consider:

- How can you find ways to be responsive when your work reveals unethical practices in an organization, or when you receive reports of problems caused by your evaluation?

- Can you make sure to give back to the participant organization involved in the evaluation?

- To whom do you owe considerations?

- Who may you be neglecting?

- What kind of power do you have in the evaluation project?

- Is doing things with your current methods OK? What may you be missing?

The kinds of ethical questions raised by Dr. Onyura are bound to increase in number and importance with time. As humanitarian and environmental crises surface around the planet, the field of evaluation will continue to face many important questions as a result. How we respond will have real impacts on communities.

Reference

Onyura B, Main E, Barned C, et al. (2023) The ‘what?’ and ‘why?’ of (un)ethical practice in evaluation: a systematic meta-narrative review & ethical awareness framework. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation. 38: 2. pp. 265-312. Available online: https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/full/10.3138/cjpe-2023-0023.